Saw that. Gotta think that the trolley track was on high ground at that terminal loop with riders stepping down as they disembarked.

What blows my mind, when looking at this same line at Five Points in 1920 is how undeveloped Raleigh was out in that direction…

The photograph depicts the Five Points intersection looking north on Glenwood Avenue c. 1920. The rail line seen on the left is the streetcar track to Bloomsbury Park.

N.53.16.6470

From the Albert Barden Collection, State Archives; Raleigh, NC.

Raleigh’s Carolina Power & Light Trolley System

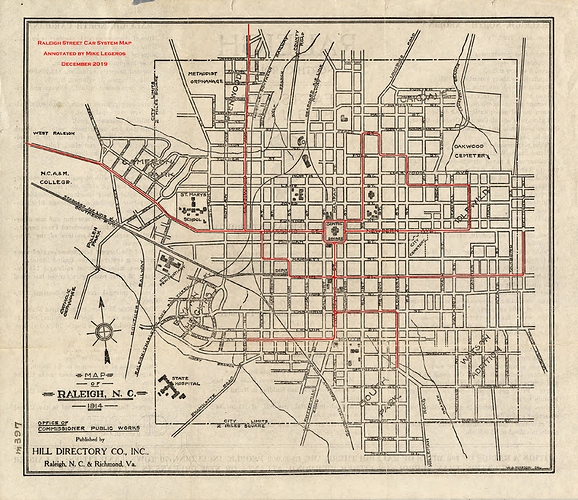

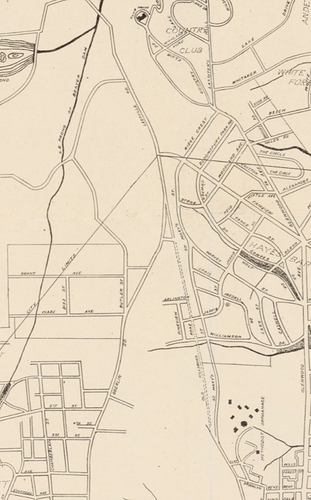

1914 map of the system (from Mike Legeros)…

And, a little more detail on the development of the area at the time…

Bloomsbury Historic District

The Bloomsbury Historic District was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2002. Portions of the content on this web page were adapted from a copy of the original nomination document. [‡]

Bloomsbury Historic District, located northwest of downtown Raleigh, is locally significant as an early twentieth century suburban neighborhood constructed during the transitional period of the late 1910s and 1920s when streetcar suburbs were giving way to early automobile suburbs. Developed on either side of Carolina Power & Light’s Glenwood Avenue streetcar line, Bloomsbury was a relatively diverse neighborhood of middle- and upper-middle income citizens. The streetcar, and by the mid-1920s, the automobile, enabled these home buyers to exchange urban life for the promise of a suburban retreat. Secured by restrictive deed covenants and equipped with electricity, water, sewer and phone service, Bloomsbury offered urban conveniences within the framework of a “safe” society. The large number of garages in the Bloomsbury Historic District testifies to the importance of the automobile in the development of the neighborhood. Physicians, attorneys, insurance agents, managers, and meat cutters all resided in Bloomsbury with little social stratification. Their dwellings represent an excellent collection of popular architecture from the early-to-mid twentieth century including numerous Craftsman Bungalows, several Colonial Revival structures and fine examples of Spanish Colonial Revival, Tudor Revival, Period Cottages and Minimal Traditional houses.

The Bloomsbury Historic District is eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places for community planning and development because it is representative of the development of early suburban neighborhoods from their conception through the transitions inherit in altering lifestyles, technologies, and postwar changes in tastes, as well as being representative of the acceptable size, use, and social segregation of early restrictive developments. Furthermore, Bloomsbury played a notable role in the suburban development in the Five Points area.

The Bloomsbury neighborhood is also eligible for the National Register for its architecture. The Bloomsbury Historic District has a significant collection of illustrative and representative examples of architectural styles from the period of significance. This collection is significant as a distinctive entity where many of the individual components are not individually notable. As a whole, the Bloomsbury Historic District is a notable collection of early twentieth century architecture: representing the architectural styles popular during the most intense periods of development: 1920-1928 post World War I with a predominance of Craftsman and the inclusion of Foursquare and Colonial Revival styles; 1935-1939 post Depression Recovery Era with Period Cottages and Revival styles popular; and, 1946-1952 post World War II when traditional derivatives, Minimal Traditional and Cape Cods made a stronger appearance.

The period of significance of the Bloomsbury Historic District extends from ca.1914, the construction date of the oldest contributing resources and the date of the plat of the neighborhood, to 1952 to include changes in development patterns and architectural styles after the close of World War II. This period encompasses the Craftsman Bungalows, Foursquares, and other styles that make up the initial period of development during the late 1910s and 1920s. Furthermore, it incorporates styles that gained greater popularity during the 1930s and after World War II and had a notable impact on the character of the neighborhood, such as Period Cottage and Minimal Traditional. Although there are fewer resources dating from the postwar era than from earlier decades, these resources contribute to a greater understanding of the overall development of the neighborhood and the changes in taste and technology indicative of post World War II society. The neighborhood continued to be developed into the 1950s and 1960s, however, this period is not of exceptional significance, and therefore the period of significance ends with the fifty-year cut-off date.

Historical Background

Glenwood Avenue intersects with Fairview Road and Whitaker Mill Road creating the Five Points intersection. Before World War I these were dirt roads that connected area farms and mills. There was scattered construction in the vicinity of this intersection consisting of a few homes and possibly a store.[1]

To the north of Five Points was the one hundred-acre Bloomsbury Amusement Park. The park was opened in 1912, northwest of downtown Raleigh on property that is currently the site of the Carolina Country Club.[2] It was operated by Carolina Power and Light Company (CP&L), who built it as an “end-of-the-line” attraction for their Glenwood Avenue streetcar. The park featured a roller coaster, a grand merry-go-round, music, a penny arcade, and an ice cream parlor.

Lit by eight thousand light bulbs, the park also served as a large-scale advertisement for the wonders of electricity.[3] While Bloomsbury Amusement Park was short-lived, it aided the development in Five Points by bringing riders through the undeveloped area. With transportation available on the streetcar, the idyllic setting naturally drew home buyers who were eager to escape the urban core.

James H. Pou, Jr., a local developer, recognized this trend and saw an opportunity in the land he owned on either side of Glenwood Avenue. A savvy entrepreneur, Pou had purchased this tract in 1905, before either Bloomsbury Park or the streetcar had arrived in the Five Points area.[4] Beginning in 1906 Pou developed the Glenwood neighborhood, one of Raleigh’s earliest streetcar suburbs, to the south of Five Points. Pou was a prolific developer throughout the early and mid-twentieth century developing the Roanoke Park and Georgetown suburbs in the Five Points area, among other ventures in Raleigh.

In 1914, Pou hired the team of Riddick and Mann, Surveyors, to lay out the Bloomsbury subdivision. C.L. Mann, was a professor of engineering at North Carolina State College and would later be involved in the platting of Hayes Barton. Pou marketed the new neighborhood to middle and upper-middle class urbanites. The advertisement and description printed on the back of the 1914 plat map promoted Bloomsbury as having “water, sewers, electric cars and lights, ‘phones.’” These were amenities thought of as necessary by city dwellers, accustomed to such accommodations. Furthermore, playing on the idyllic character of the area, Pou announced: “Land high, rolling, and perfectly drained. Surroundings fine. No malaria, nuisances or bad neighbors. In brief, the terrain is without a fault.” Of even greater importance to would-be suburbanites during this era was the assurance that their new home would remain the quiet, country retreat they envisioned. In Bloomsbury, covenants delineating the race of occupants, the cost of dwellings (not less than $2,000), house setback, the keeping of livestock, and a moratorium on commercial or industrial development (with the exception of the triangular lot 79, which by the mid 1920s would be the site for the Flat Iron Building) gave buyers confidence in the long-term character of the neighborhood. Pou went even further, pointing out that three of the Bloomsbury sections were “doubly restricted;” being restricted themselves and lying to the west of the restricted subdivision of White Oak Forest.[5]

Bloomsbury incorporated some sparse development that had sprung up along the streetcar line. The 1914 plat map, modified in 1916, shows that four houses were already scattered along Fairview Road, four were clustered near Five Points on Glenwood Avenue, six houses had been built on White Oak Road near Glenwood, and four, very small, dwellings were located on Whitaker Mill Road. The Glenwood and White Oak houses may have been those built “on spec” by C.V. York in 1914 as part of his effort to persuade CP&L to give hourly streetcar service to the Five Points area.[6]

The importance of the streetcar line to the new subdivision is indicated in the description of Bloomsbury on the plat map. The advertisement announces that the neighborhood had 6,000 feet of frontage “on [the] car line” and that “no lot [was] over three minutes walk from the car line.”[7] This equality of location was born out in the heterogeneous character of the neighborhood.

The inhabitants of The Circle (formerly Bloomsbury Circle) were especially diverse in 1925. Living side-by-side was a life insurance agent, an attorney, a flagman, part-owner of a roofing company, and a meat cutter. Likewise, Creston Road was inhabited in 1930 by an optometrist, a meat cutter, a physician, two engineers, a division freight manager, and the industrial agent for CP&L. While the houses located on Glenwood Avenue could not be termed “grand,” they do tend to be some of the larger houses in the Bloomsbury Historic District. Yet, in 1925, the street was home to a relatively diverse group including an auditor, a yard master, a bookkeeper, a pharmacist, a state bridge engineer, an attorney, an insurance agent, and a postal clerk. Overall, Bloomsbury was a middle and upper-middle class neighborhood during its early years with a wide range of occupations represented. The Circle and Crescent Street appear to have been the most diverse in terms of income levels, while streets such as White Oak Road were patently middle class with inhabitants such as a bank cashier, a traveling salesman, a concrete contractor, and the owner of Rand Grocery Company.[8]

Delayed by World War I and the economic slump that followed, development in Bloomsbury, and the Five Points area generally, was most intense during the mid- and late-1920s. Several factors came together in the 1920s allowing the neighborhood to expand dramatically. These included the development of the prestigious Hayes Barton neighborhood to the east, the extension of the city limits during the early 1920s promising municipal utilities, the presence of the streetcar, and the increased affordability and popularity of the automobile.

Bloomsbury clearly began as a streetcar suburb, but its development in the 1920s was during a significant transition period in transportation. The advertisement printed on the 1914 plat hinted at the transitional period in which the neighborhood was constructed. “Fronts half mile on the Asphalt Road, part of the National Highway,” the ad announced. The National Highway is believed to be present-day Fairview Road and the announcement of Bloomsbury’s frontage on it indicated that good roads for automobile transportation were also important to neighborhood’s success. The 1920s saw the gradual decline in streetcar riders culminating in the discontinuance of streetcars in favor of gasoline-powered buses in 1933.[9] The impact of the automobile in the Bloomsbury Historic District is clearly seen in the large number of existing garages within the district.

As more families purchased automobiles, it became even easier to locate in the suburbs. In Raleigh, a building boom occurred in the Five Points suburbs. In the 1920s, 270 houses were constructed in Bloomsbury, as compared to 75 during 1931-1941 and 90 during the post-1945 period.[10] In fact, most of Bloomsbury was developed during the 1920s, especially those sections nearest the Hayes Barton development, between Fairview Road and Glenwood Avenue in addition to the inner ring of The Circle and the area south of Alexander Road. The northeastern corner of the neighborhood developed last. By 1928, the only street within the Bloomsbury Historic District that did not appear on the city map was Byrd Street (although it appeared as Bloomsbury Park Road on the original plat for the neighborhood). Construction had come nearly to a standstill during the Depression, but regained strength after 1935, and by 1939 Byrd Street had been added to the city street map.[11] Recovery Era and immediate postwar development (c.1946-c.1952) occurred primarily in the northeastern corner of the neighborhood and by 1952 the district was substantially built-out.[12]

Commercial activity followed the residential development of the 1920s. The Flat Iron Building (1801 Glenwood Avenue), constructed in 1922, is one of the earliest existing commercial buildings in Five Points. It originally housed a grocery store ran by Mr. Allen. An important feature of the store was a gas pump, believed to be the first in Five Points. The building later housed Gattis’ Drugstore.[13] By the 1950s, other commercial buildings, such as the Wachovia branch bank had created a larger commercial nucleus at the Five Points intersection.

While there is relatively little development in Bloomsbury dating from the 1960s, the duplexes and quadraplex located on The Circle indicate the continued social diversity in the neighborhood. The neighborhood was generally intended to be occupied by a prescribed economic elite, though City Directories showed a relatively diverse mix of economic levels early in Bloomsbury’s development. The inclusion of multi-family units in the neighborhood furthered this trend by affording residents of a relatively lower economic level an opportunity to live in the area, if not own.

By the late 1970s, the neighborhood, once slightly out of fashion in an era of ever-expanding suburbs, had begun to regain favor. Hales Road was extended into a cul-de-sac (not included within the district boundary) during the 1970s and 1980s and elaborate Colonial Revival dwellings were constructed there. Today, the neighborhood is very popular for those seeking in-town housing. This popularity and the neighborhood’s proximity to the highly desirable Hayes Barton neighborhood have created a situation where few people realize that Bloomsbury was an individual suburb, platted prior to Hayes Barton with a distinct history that represents an important time of transition between the streetcar and the automobile.

The Bloomsbury Historic District contains a diverse collection of both standard and custom houses encompassing the popular architectural styles of the time. The Craftsman style, or variations on that style, are widespread in both small bungalows and larger residences. Likewise, the Colonial Revival style is pervasive with many notable examples of Dutch Colonial Revival, as well as the more unique Spanish Colonial Revival. Bloomsbury Historic District also has a collection of Foursquare forms, that are often detailed with Craftsman and Colonial Revival influences. The Bloomsbury Historic District is also well-represented with the Period Cottage and Minimal Traditional styles, as well as several homes that combine combinations of styles typical of the first half of the twentieth century.

Endnotes

[1]Luther Hughes, “Five Points as recalled by Mr. Luther Hughes, Hayes Barton Baptist Church, c.1975,” in Architectural Survey File “Hayes Barton National Register Historic District, 1991 and 2001,” State Historic Preservation Office, Raleigh.

[2]Helen Ross, “Bloomsbury — Survey Area XIII, 1991” in Architectural Survey File “Bloomsbury National Register Historic District, 1991 and 2001,” State Historic Preservation Office, Raleigh.

[3]David Perkins, ed., Raleigh: A Living History of North Carolina’s Capital (Winston-Salem: John F. Blair, Publisher, 1994), 128.

[4]Riddick and Mann, surveyors, “Complete and Final Map of Bloomsbury, 1914,” reverse side of map.

[5]Riddick and Mann, reverse side of map.

[6]Perkins, 109.

[7]Riddick and Mann, reverse side of map.

[8]Raleigh City Directories: 1925 and 1930.

[9]Ross, “Bloomsbury.”

[10]Ross, “Bloomsbury.”

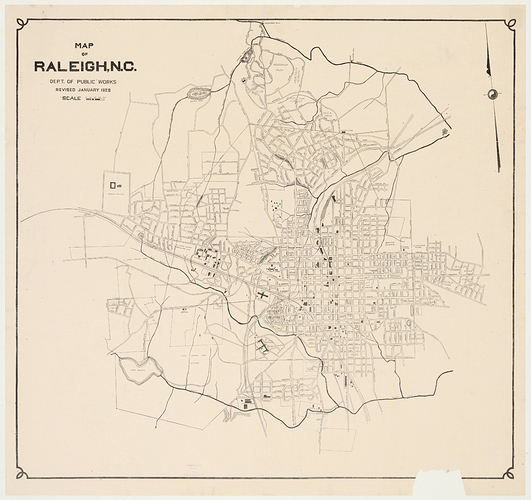

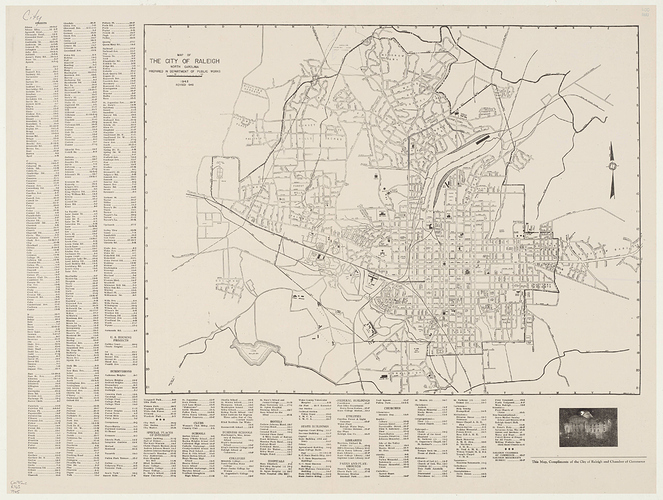

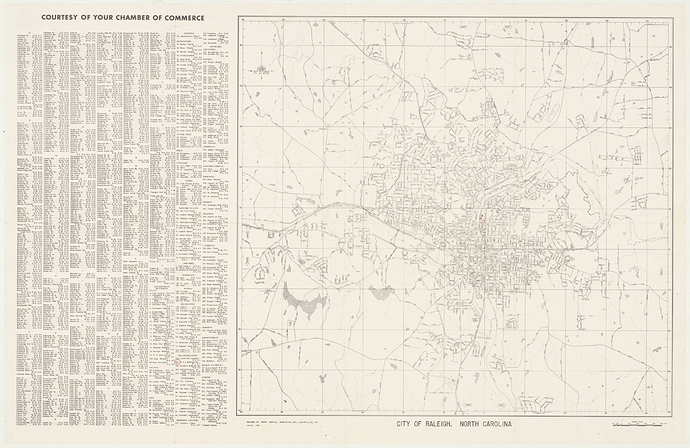

[11]Chamber of Commerce, “Map of Raleigh, N.C., c.1928;” Raleigh Department of Public Works, portion of 1939 Raleigh city map, photocopy; and Ross, “Bloomsbury.”

[12]Raleigh Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps 1914, updated in 1926, 1928, 1939, and 1949.

[13]Hughes.

References

Chamber of Commerce. “Map of Raleigh, N.C., c.1928.”

Hughes, Luther. “Five Points as recalled by Mr. Luther Hughes, Hayes Barton Baptist Church, c.1975” in Architectural Survey File “Hayes Barton National Register Historic District, 1991 and 2001.” State Historic Preservation Office, Raleigh.

Perkins, David, ed. Raleigh: A Living History of North Carolina’s Capital . Winston-Salem: John F. Blair, Publisher, 1994.

Raleigh City Directories.

Raleigh Department of Public Works. Photocopy of portion of Raleigh City Map, 1939.

Riddick and Mann. “Complete and Final Map of Bloomsbury, 1914.”

Ross, Helen. “Bloomsbury — Survey Area XIII, 1991” in the Architectural Survey File “Bloomsbury National Register Historic District, 1991 and 2001.” State Historic Preservation Office, Raleigh.

Ross, Helen. “Georgetown-Survey Area X, 1991” in the Architectural Survey File “Roanoke Park and Georgetown — General Information, 1991.” State Historic Preservation Office, Raleigh.

Ross, Helen. “Hayes Barton — Survey Area XII, 1991” in the Architectural Survey File “Hayes Barton National Register Historic District, 1991 and 2001.” State Historic Preservation Office, Raleigh.

Ross, Helen. “Roanoke Park — Survey Area IX, 1991” in the Architectural Survey File “Roanoke Park and Georgetown — General Information, 1991.” State Historic Preservation Office, Raleigh.

Sanborn Map Company. “Raleigh, N.C., 1914.” Map updated 1926, 1928, 1939, and 1949.

‡ Sherry Joines Wyatt, Historic Preservation Specialist, David E. Gall, AIA, Architect, Bloomsbury Historic District, Wake County, NC, nomination document, 2001, National Park Service, National Register of Historic Places, Washington, D.C.